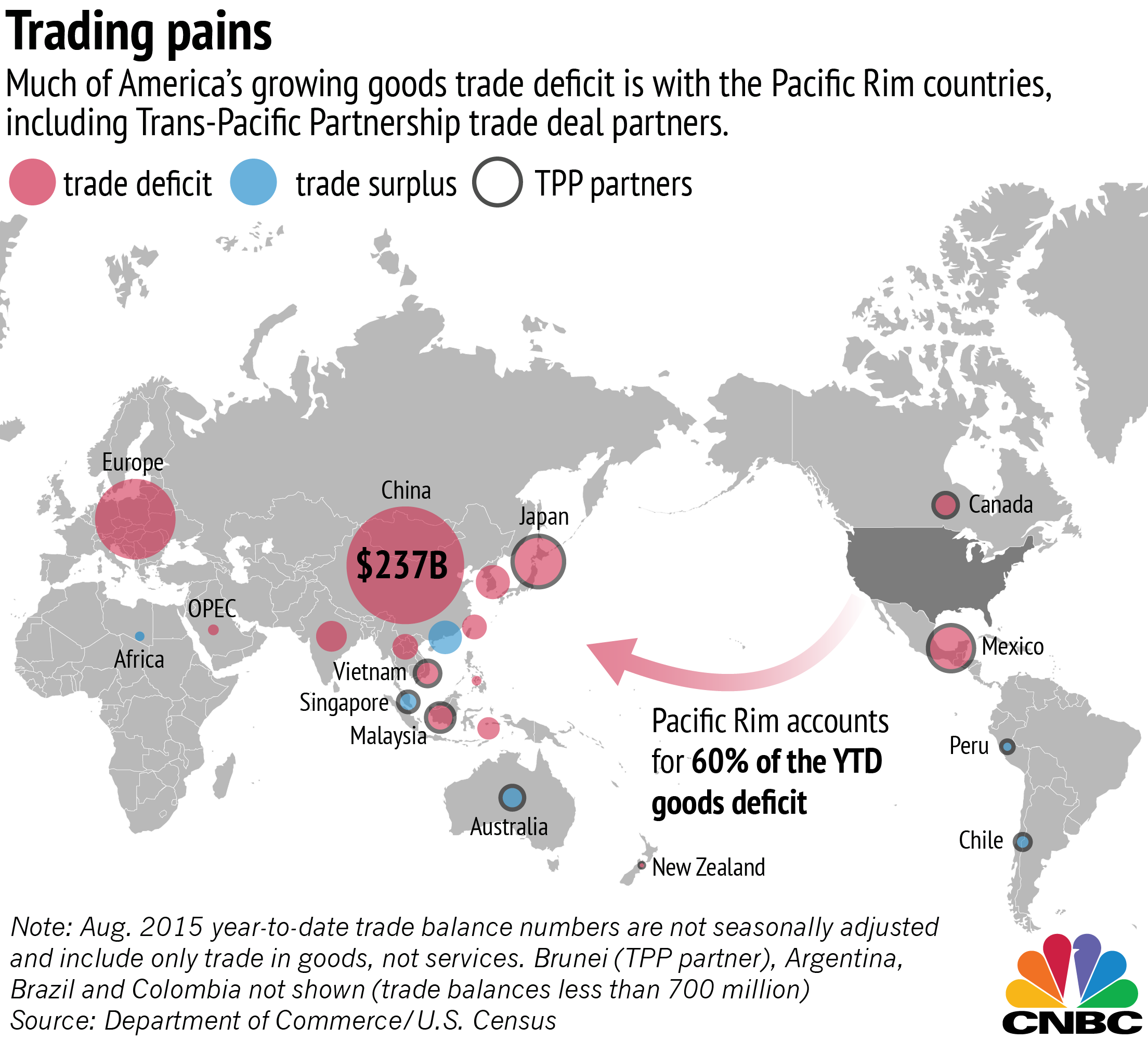

President Barack Obama signed a major free trade deal Monday between the U.S., Canada, Mexico and nine other Pacific countries. New data released Tuesday were a reminder of how imbalanced most of those trade relationships are.

America's monthly trade deficit rose nearly 16 percent in August, according to data from the Department of Commerce. That seasonally adjusted $48.3 billion brings the country's running trade deficit year to date to $354 billion for goods and services and more than $500 billion for goods alone.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement is designed to remove barriers for American business abroad, including more than 18,000 tariffs on American goods in the participating countries, according to the administration. Six of those countries currently sell more to the U.S. than they buy. Overall, they account for $103 billion, or about 20 percent, of the nation's trade imbalance.

The deal is widely expected to boost American exports and real income, but its effect on the overall trade balance is contested.