The Beijing offices of Avenues: The World School are cavernous yet sleek, occupying a high-rent complex designed to look like a dragon - a seven star hotel is in the "tail," Avenues, like IBM, is in the "head," overlooking Beijing's Olympic Park, Bird's Nest Stadium and Water Cube, the crown jewels of 2008's $44 billion Olympics construction boom.

But, like the derelict structures left over from the Olympics building craze, the Avenues office is largely empty. Although the school had planned to open what was to be only its second campus worldwide in September 2016, partnerships have unraveled, permits lag, and nobody will put a date on when the school will open its doors to students able to afford the $40,000-plus tuition fees.

Fortunately, Avenues' American backers, led by mid-sized private equity firms, seem to possess a quality rare for such entities: patience.

"We are not advertising we are not trying to be out in the community yet," said Mike Levy, who will head the Avenues Upper School in Beijing and is overseeing the opening of the campus in the meantime. Levy, who has written an acclaimed book on teaching in China, told CNBC he doesn't know when the school will open. "To open a school at the scale that we plan, you have to be really careful and really thoughtful."

Players ranging from local private equity funds including Baring Private Equity Asia, Qiming and CITIC, to early stage investors such as ZhenFund, have been dabbling in the financing of private schools in mainland China, many of them drawn by potentially vast demand for international-style curriculum from Chinese parents eager to prepare their children to venture overseas for university.

Schools, Asia Venture Capital Journal points out, make for alluring investments: their student customers are loyal for years and pay in advance, while the best of the type possess prestige and international pedagogy and curriculums; attributes that are hard to copy.

But in China, the academic prowess and prestige necessary to win over demanding parents comes at a ponderous pace, that can be ill-suited to equally demanding private equity fund investors.

"The space is wisely undertaken by the experienced," warns Kim Morrison, chief operating officer at Grok, an international education consultancy. "It's a market that is changing really quickly. I think consumer preferences are going to change very quickly. [And] it's still highly subject to regulation."

In 2012, when Avenues opened its first campus, in New York, with $75 million in funding from New York's Liberty Partners and LLR Partners of Philadelphia, the school, which planned to have 20 campuses worldwide by 2021, made waves.

New York parents were both awed and skeptical of the school's $40,000 tuition, high-tech dual-bilingual immersion programs in Spanish and Mandarin, the for-profit business model led by some of the country's more controversial education entrepreneurs, research and development department headed by a NASA statistician and, perhaps most of all, by the school's belief - hubris to some – that it could take on the often stuffy old guard of some of America's most storied prep schools.

But, in Beijing, where bilingual immersion, plush campuses designed by famous architects, and sky-high tuition are par for the course, the grand academic and financial ambitions of Avenues hardly raise an eyebrow. Nor does the funding model. Though some would say it should, because the barriers to achieving those ambitions are unusually high.

Private international schools in China that do not admit Chinese nationals, such as the five British international schools run by Nord Anglia Education, which was taken private by Baring Private Equity Asia in 2008, have far less red tape to contend with than those - fewer than 60 schools in all of China - that do.

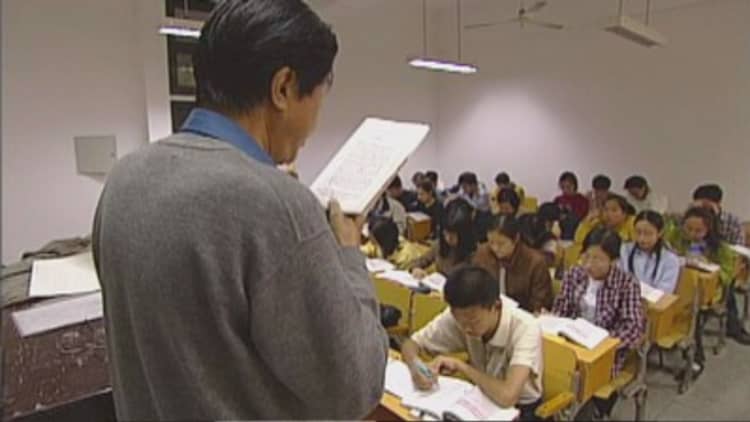

In order to accept local students, as Avenues would like to do, such schools must incorporate China's rigorous compulsory core curriculum, which requires that children study an officially approved history course, topics of "morality" and to be able read and write thousands of Mandarin characters by the ninth grade. State regulators must vet everything about the school, down to whether it serves vegetables raw or steamed.

In exchange for their efforts, schools approved to admit Chinese children have access to the country's 100 million students, not just the niche market of expatriates and foreign passport-holding Chinese citizens, a tantalizing prospect for investors and ambitious educators alike.

Private education institutions backed by longer-term investors have made it work, usually with after-school or pre-school programs. A few have managed to win approval to teach from kindergarten through ninth grade (known as K-9), the years for which the compulsory curriculum applies.

"If it were just about starting a school it would get boring ," said Jack Hsu, chief executive of the Ivy Group, a network of kindergartens that expanded into the K-9 space this year. "We want to touch the lives of 100 million students."

But the time this takes may be anathema to private equity groups, who are obliged to bring investors returns now rather than in the 10, 20 or more years it can take for a school to thrive anywhere, both Hsu and Levy said. Perhaps more so in China, where the concept of private schools is still new and, until recently, limited to semi-legal slipshod institutions attended by domestic-migrant children unable to obtain the official resident status necessary to attend public schools.

For years the Beijing equivalent of the world's Etons, Brearlies and Grotons have been a select handful of state schools, made plush with money from powerful parents and state-owned companies that paid to reserve seats for the children of employees.

Replicating this in the timeframe required by private equity has been a painful two-year learning period for Avenue's Levy, as a promised partnership with a top local school unraveled, negotiations with officials for approval to teach local students dragged on and efforts to insure sound construction processes in a national industry rife with scandal (not least of which are shoddily made schools such as those that collapsed in 2008's Sichuan earthquake, leading to the deaths of thousands of children.

Ivy's Hsu has had the luxury of a decade to see out the difficulties of establishing a private school in China, thanks Ivy's backing from Singaporean wealth fund Temasek, which is known for its patience in seeing investments come to fruition.

"We are lucky because we have strong financial backing and at the same time none of that pressure," said Hsu. "There is no time horizon. Their only mandate was to build a quality education program."

Hsu says he is constantly being wooed by private equity funds hoping to invest in Ivy schools. He meets with them and hears them out – the business is, after all, "capital intensive," in his words. Most, though, are looking for returns within three to four years. Hsu says he needs at least seven to make a school pay.

His strategy has proven solid. When the first Ivy-created kindergarten opened in Beijing's embassy district twelve years ago, all but a few of its 16 students were foreigners. Today, with 3,400 students across 17 schools in four cities, 90 percent of the student body is local.

With deep local roots and a rigorous Mandarin program, Ivy's Daystar school in the suburb of Shunyi has drawn Chinese parents who want their children to have the option to attend a public high school and ace the country's infamously difficult university entrance exam. Where is Daystar?

Daystar is a little more than half the price of Avenues and other schools such as Keystone, a non-profit backed by low-interest loans from unnamed "founding benefactors," and Hui Jia, a privately owned school that did not return CNBC's phone calls and emails about its funding model, that offer bilingual international programs to local students alongside perks like horseback riding, gold medalist swim coaches and administrators poached from New England prep schools. But parents who could afford those schools have chosen Daystar instead.

Bureau of Education officials have also taken notice when they have visited to observe Daystar's implementation of the compulsory core curriculum.

"When they see even the little blond kids are getting high scores on tests, they ask, are you drilling them every day?" said Hsu. "I tell them, no, and they say, well how are you doing it?"

But even this seemingly stellar performance, and at a lower price tag, hasn't blunted the expectations of parents. In a country where food scandals seem to unfold at least once a season – the carcasses of pigs clogging a shanghai river, avian flu, killer baby formula and heavy metals in honey – school lunch is high stakes.

Daystar's food consultant travels to the farms where each ingredient is sourced, once flying to southern Yunnan Province just to look at mushrooms.

Such attention to detail comes at a cost and perhaps it is telling that Temasek diversified its investments in the mainland education sector of late, with a move in something other than bricks-and-mortar. Recently, the fund participated a $100 million funding round for education app 17zuoye.com, a name which translates to "homework together." The app contains English and math lessons aligned with the national curriculum on a platform through which teachers, students and parents can interact.

Founded in 2011, the app now covers more than 10,000 Chinese public schools, a pace of development even private equity would find acceptable.