Being reduced to eight Supreme Court justices after the death of Antonin Scalia doesn't necessarily mean the court is doomed to months of unproductive gridlock.

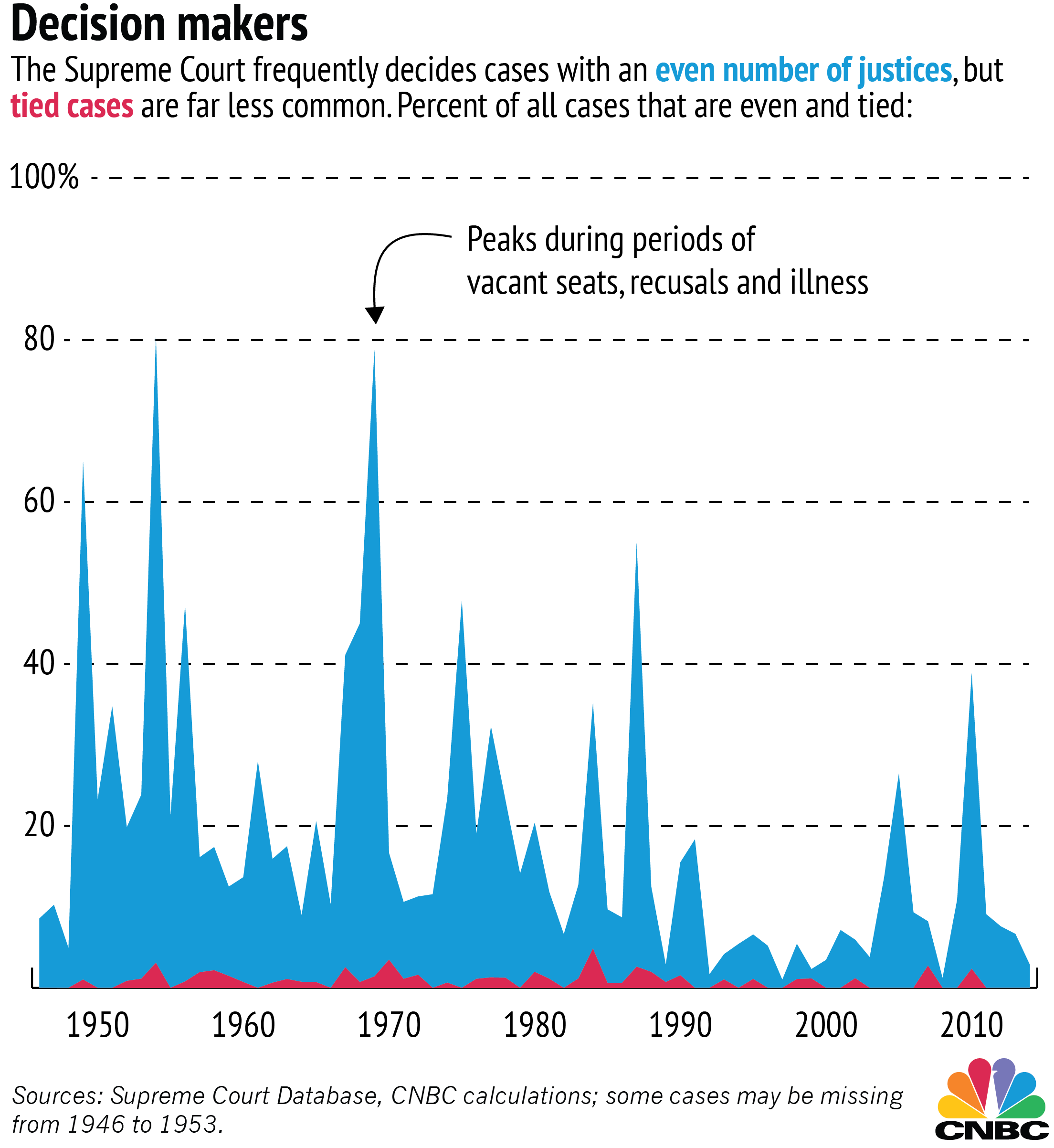

In fact, an evenly split court really isn't anything new. As Justice Samuel Alito pointed out last week, the court has had an even number of justices in the past. Nearly 1 in 5 decisions passed down since 1946 were decided by an even number of votes, according to a CNBC.com analysis.

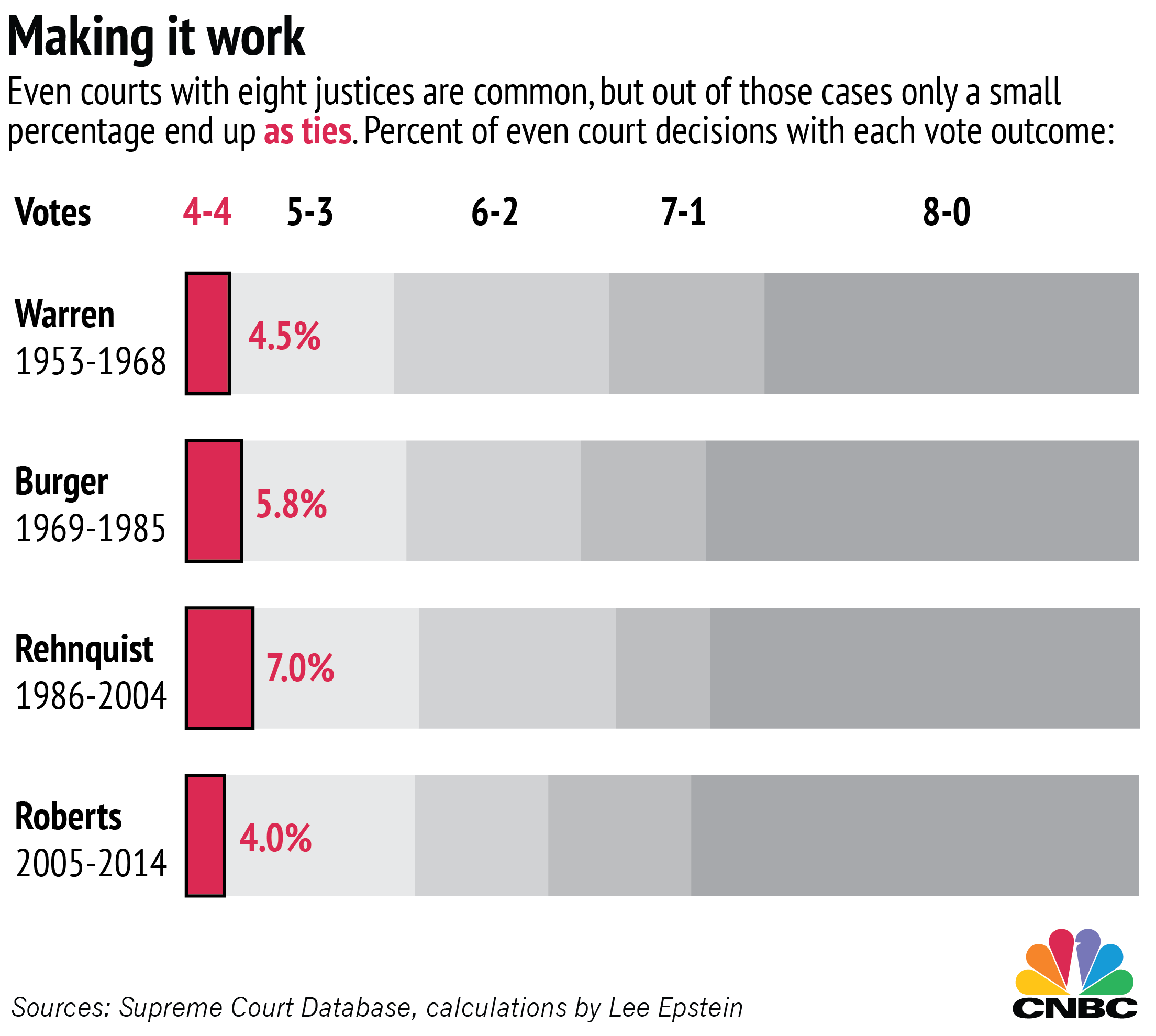

Evenly split courts, which are usually caused by a recused justice or a temporary empty seat, are common, making about 19 percent of all decisions. Yet only 5 percent of those decisions have been ties, suggesting that most courts manage to secure a majority one way or another.

According to the historical data back to 1946 from the Supreme Court Database, there have been no tied cases since 2010, despite more than 20 even courts.