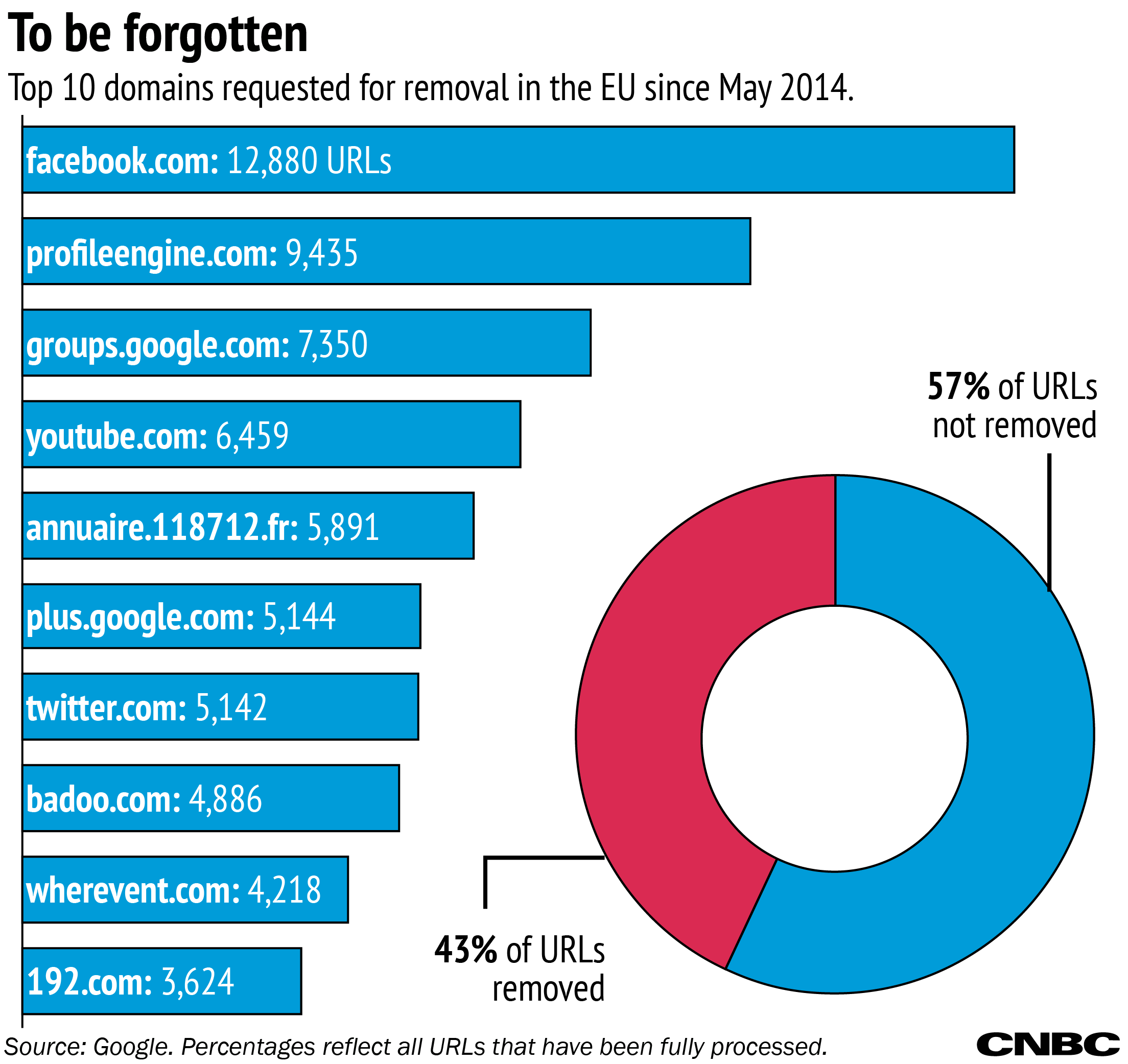

For two years now, Google has been "forgetting" Europeans.The number one place that Europe wants forgotten? Facebook.com.

Sunday marks the second anniversary of Google accepting requests to remove certain URLs from its search results if an individual requests it — otherwise known as the "Right to be Forgotten" ruling based on the European Union's data-protection rules. It allows individual Europeans to fill out a form with Google, requesting that specific internet addresses be removed from search results if they contain inaccurate or outdated information about them.

Google's process in determining what links to remove from search results is set up under EU guidelines to protect citizens' data. Decisions are often based on details about the situation and the person, as evidenced by example cases from the company's transparency report. In one, a teacher requested removal of an article about a decade-old conviction for a "minor crime." Google removed those links from search results for the teacher's name.

In another, a public official requested removal of a "recent article discussing a decades-old criminal conviction." In that case, Google did not remove the links.

Google also rejected the request of a former U.K. clergyman who had been accused of sexual abuse under his professional capacity. News articles about the investigation remain in his search results.